Software As If People Mattered

“We do not ride upon the railroad; it rides upon us,” Henry David Thoreau wrote in Walden, his most well-known work. He reached this conclusion contrasting the thunderous roar of the passing train to his quiet, solitary existence during his two years at Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts.

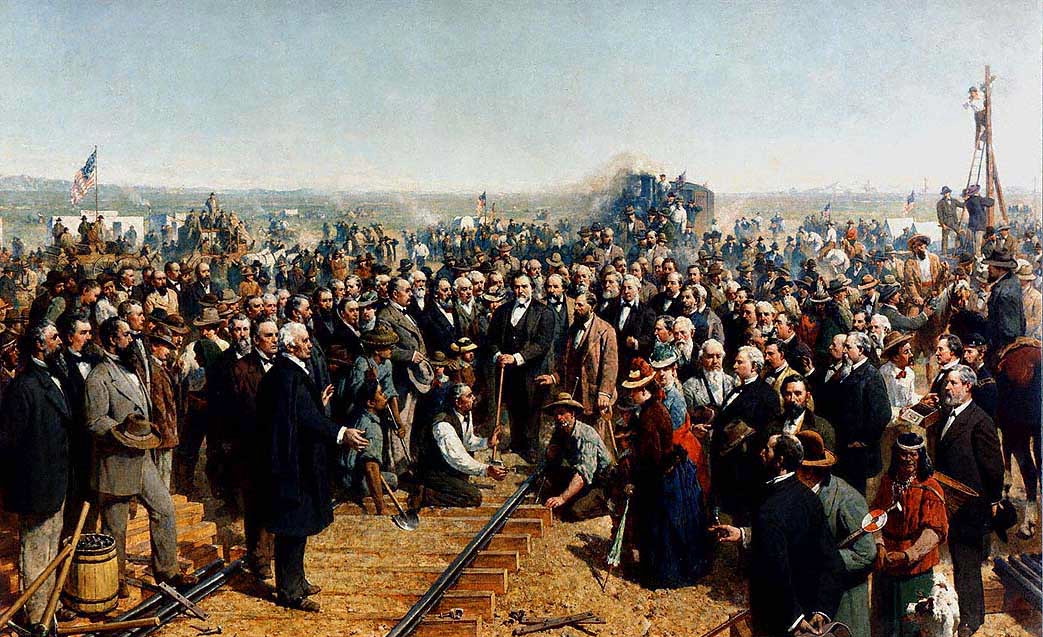

Thoreau wrote Walden between 1845 and 1847. These were early days for the trains, and their transformation of American life had only just begun. It would be another twenty-two years before the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, which would alter the country—and mankind—forever, proving Thoreau’s observation quite prescient.

In his 1964 book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, Canadian academic Marshall McLuhan introduced the now famous phrase “the medium is the message.” What McLuhan meant was that the medium through which content is delivered ultimately has much more influence over societal and cultural change than does the message itself, despite our focus on the latter. The most significant effects of technology occur not at the “level of opinions or concepts,” McLuhan stated, but rather they alter our “patterns of perception.”

As American journalist Nicholas Carr summarized in The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, new technologies and methods of communication “mold what we see and how we see it—and eventually, if we use it enough, it changes who we are, as individuals and as a society.” After technology is created, essentially, it takes on a direction of its own, altering us in ways that may never have been imagined or intended, a concept formalized as technological determinism by economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen.

McLuhan used the railroad as an example of his concept, noting that it “radically altered the personal outlooks and patterns of social interdependence.” By far, the biggest impact was that it ushered in an era of bigness and speed that has persisted ever since.

That bigness and speed spawned numerous further inventions, perhaps the most significant of which was the standardization of time. Before it was possible to travel far quickly, each town generally kept its own local time. Railroads necessitated establishing a shared representation of time, resulting in the establishment of Greenwich Mean Time in the United Kingdom in 1847 and the North American time zones in the United States in 1883.

So the railroad did not just make it possible for us to send messages or goods or even ourselves across great distances. It fundamentally changed the way that we perceive time and space and our place in the world.

Today’s equivalent is, of course, software, the internet, and going forward, AI.

The early internet promised us a new era of decentralization, connection, and creativity. It has done anything but.

The hackers of the internet’s first days envisioned the web as a force for individualism and autonomy. That vision persisted through the first decade of its widespread adoption. In 2006, Chris Anderson published The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More, detailing how this was playing out in the business world. He pointed to successes like Amazon and Apple’s iTunes as showcasing how the internet made it economically viable to offer customers a long-tail of niche products that simply wasn’t possible for those products’ brick-and-mortar equivalents. He confidently declared that the age of mega-hits was over, and that the internet would give consumers more choice to pursue their individual interests and producers the option to make a living without requiring a massive audience.

Of course, that’s not how things have worked out. If anything, virality and consolidation are the defining characteristics of the internet age, more important than ever before. On paper, Anderson’s theory still makes a lot of sense. The internet should make it economically possible to sustain businesses catering to niche interests. So why didn’t it happen? McLuhan has the answer, I think. What neither Anderson nor many of the nerds who pioneered the web considered is that the internet would also change our tastes. In a world where we are constantly aware of what everyone else is doing-and where we have little privacy to pursue our own interests outside others’ gazes-consumers shifted even more towards conformism. The internet did not just change the nature of supply, as originally envisioned. It ended up significantly altering the nature of demand as well.

There is little doubt that the internet is changing us at a fundamental level and in ways that aren’t very pleasant. Our attention spans are shortening to the point a goldfish would raise an eyebrow. We are losing our ability to be contemplative and thoughtful, instead succumbing to rage at the latest clickbait headline. We are losing our ability to be agentic and proactive, instead responding in a flurry of reactivity, decisions delegated to our algorithmic overlords. We feel increasingly unhappy, alone, and purposeless, and yet they try to convince us the solution is even more of the same.

Unfortunately, this isn’t just an accident or a misunderstanding. Most software today is carefully engineered to prey on fundamental aspects of our biology and psychology that bring out our worst characteristics and tendencies. It keeps us constantly distracted, anxious, and at odds with one another. It tracks our every move and thought and uses these details to manipulate us. It monetizes our deepest fears and insecurities, constantly reminding us how much better everyone else is doing.

If Thoreau were alive today, it’s almost certain that he would say that we do not use our software; it uses us.

In his 1973 book Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered, British economist E.F. Schumacher wrote “if that which has been shaped by technology, and continues to be so shaped, looks sick, it might be wise to have a look at technology itself. If technology is felt to be becoming more and more inhuman, we might do well to consider whether it is possible to have something better-a technology with a human face.”

Schumacher felt that the “idolatry of gigantism” which had become ubiquitous in the 20th century was leading to a breakdown in social order—a “footlooseness,” as he called it, that “produces an appalling problem of crime, alienation, stress, social breakdown…the result is a ‘dual society’ without any inner cohesion, subject to a maximum of political instability.” He also had grave concerns on the effects of mass production on the nature of work, stating that “soul-destroying, meaningless, mechanical, monotonous, moronic work is an insult to human nature which must necessarily and inevitably produce either escapism or aggression.” He viewed work not only as an economic concern but as a spiritual one, and he worried about a world in which the majority of people lacked a profession they felt any meaningful connection to.

The “technology” Schumacher referred to was that of an earlier age—heavy machinery and transportation—but it’s our digital revolution that has truly showcased his wisdom. Our online worlds create estrangement even without the physical separation of Schumacher’s footlooseness. And the exhausting and pointless performance of modern office work—endless Zoom meetings and Slack messages and emails—is so far from “good for body and soul” as to make us jealous of the factory workers Schumacher felt so sorry for.

Schumacher did not share McLuhan’s belief in technological determinism. Rather, he was confident that societies could choose how to apply technological advancement, saying “I have no doubt that it is possible to give a new direction to technological development, a direction that shall lead it back to the real needs of man, and that also means: to the actual size of man. Man is small, and therefore small is beautiful…[redirecting] technology so that it serves man instead of destroying him requires primarily an effort of the imagination and an abandonment of fear”

I am not as confident as Schumacher that we can change course on a large scale. I’m just not sure that we can escape humanity’s predilection for scale and speed and more, more, more.

But I am confident that some of us, as individuals, can and should make that choice. We can choose to turn off our notifications and focus on our real lives. We can choose to use tools that foster genuine social connections instead of consuming endless 15-second clips from people we will never meet. We can choose to consume news in a considerate and more slow-paced manner. We can choose to ignore the endless barrage of junk emails trying to sell us stuff. We can choose quality over quantity when it comes to our tech. We can still make good on tech’s original promise.

We needn’t entirely give up our phones, our apps, our quest to put a man on Mars, or any of our other technological ambitions. But we should be more thoughtful about which tools we use, why we use them, how we use them, and of the ways in which they are changing who we are. As Kirkpatrick Sale puts it in his Human Scale Revisited, “the question is not of eliminating technology but of deciding which kind of technology should prevail, which of society’s values it should express.”

Software may be eating the world, but we don’t have to just stand by idly as we’re made into its lunch.

If you are, like me, not just a consumer but also a builder of software, then you can make a decision to give more people the choice to use better technologies, by making them.

And so if you would also like to change directions, then consider this a call to build and support better software. Software that is saner, calmer, and smaller. Software that supports our creativity and sovereignty. Software that seeks to bring out the best in its users rather than the worst. Software with a human face. Software as if people mattered.